Volker Bertelmann

9 pieces at nkodankoda sheet music library

over 100k editions from $9.99/month

Hassle-free. Cancel anytime.

available on

nkoda digital sheet music subscription

Editions

Annotate

Library

Perform

100k+ available Editions

More about Volker Bertelmann

He's a "sound searcher", says pianist and composer Volker Bertelmann, alias Hauschka, about himself. This search began for Bertelmann inside his piano, preparing it with drawing pins, table tennis balls, rubber erasers, any material imaginable, and so transforming it into an analog, mechanical synthesiser. Improvisation on a piano that can sound like a drum, then like an electronic effects device, like a tin or a gamelan orchestra – while all the time reminders of a romantic nocturne float by –, is still the basis of Bertelmann’s music today. But since his 2005 album "The Prepared Piano", the sound searcher has steadily extended his musical space; "Room To Expand", the title of his fourth album, speaks for itself. And so it was really only a matter of time before his sound searching led Bertelmann to that most sophisticated of all sound bodies, the big symphony orchestra. The orchestral works, just published by Bosworth, trace a part of the road Bertelmann travelled from the 10 finger orchestra of the prepared piano and the album format, to the heavy gear and the extended form. "Madeira" and "Children" had already been arranged for a chamber ensemble on Hauschka's album "Foreign Landscapes" (2010); "Penn Station" arose from the orchestration of an unpublished piece for a string quintet. "Puppen" in contrast exceeded the constraints of the 5 minute track right from the start, the piece was composed as an overture for Kevin Rittberger's play of the same name. With his latest composition "Cascades", Bertelmann has finally produced a work conceived as a large triptych for orchestra and choir. Long-standing fans of Hauschka's poetically fragile prepared piano sounds have always had something to learn with each new album; "Abandoned City" from 2014, for example, sounds a lot gloomier and weightier than anything known from this artist up to then. With the orchestral works, another a new facet of Bertelmann's music has now been added: the monumental. In "Penn Station", for example, a typical Hauschka melody achieves almost Bruckneresque sound dimensions with the four horns in unison. But even though the sound of Bertelmann’s music changes from project to project, a certain view of the world, which manifests itself in tones, remains the same. Bertelmann summarised these constants of his sensitivity in four words: "beauty, ephemerality, melancholy and absurdity." His domain is the densely atmospheric mood landscape; many of his pieces resonate with a romantic yearning – and not just because their composer seems to have a liking for minor keys. Bertelmann’s music is for the most part restlessly in motion, but it never arrives anywhere, or – to be more accurate –, it's always already there. The music revolves in circles; repetition is its building block. From short, memorable phrases, constantly repeated, Bertelmann puts together a rhythmic mosaic of small pieces. In detail, his music is finely chiselled and on the move; as a whole it seems almost static. […] There, where the composer builds up imposing crescendos again and again, like in "Puppen", everything flows to an end in a simple, soft cadence of unmatchable brevity. The fundamental, melancholic feeling of being in a state of floating, somewhere indefinable between loss and departure, was the subject of Bertelmann's to date most comprehensive orchestra work "Cascades". Significantly, this triptych starts with the end. Loss, death, stand here at the beginning. The words "Nothing left. I lost everything." are spread by the choir in countless repetitions in a wide layer. For the middle part "From Ashes", the sound searcher Bertelmann found an icily cold, crystal-clear string sound. The final movement "Perspective" for orchestra and choir is then anything but a celebratory symphonic finale. The music puts a question mark at the end of the optimistic words the text "Now, now future’s coming", the choir gets lost in unarticulated murmuring. "In this way 'perspective' is at the same time the start of loss", writes the composer. Beginning and end come together, another circle closes. (Photo © Carsten Sande)

Volker Bertelmann sheets music on nkoda

Edition/Parts

Composer/Artist

Part

Source

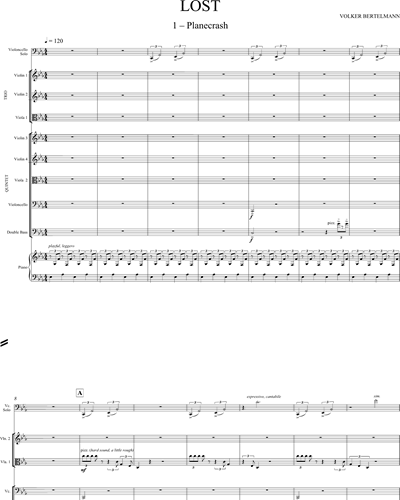

Lost

Volker Bertelmann

Full Score

Bosworth & Co

Drowning

Volker Bertelmann

Full Score

Bosworth & Co

Materials

Volker Bertelmann

Full Score

Bosworth & Co

Homeless

Volker Bertelmann

String Quartet

Bosworth & Co

Oneness

Volker Bertelmann

Ensemble

Bosworth & Co

Union Square

Volker Bertelmann

String Quartet

Bosworth & Co

World Citizen

Volker Bertelmann

Piano Quintet

Bosworth & Co

Trost

Volker Bertelmann

String Quartet

Bosworth & Co

Fifteen Million Acres

Volker Bertelmann

Mixed Chorus SATB & Ensemble

Bosworth & Co

INSTITUTIONAL PARTNERS

PUBLISHERS PARTNERS

TESTIMONIALS